The myth perpetuated by government and academics – and echoed in the media – is that the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board’s (PMPRB’s) current price control regime was somehow structured to go easy on patented drug prices in exchange for significant R&D commitments. The upshot being that since the R&D commitments have long expired and R&D expenditures as a ratio to sales have fallen, it is time for the PMPRB to bring the hammer down on drug prices by limiting Canadian prices to the median of twelve lower priced OECD countries as part of a new suite of punitive pricing regulations and guidelines. The problem is the underlying “R&D” premise is a pernicious myth – the PMPRB price control regime was never tied to levels of pharmaceutical R&D.

It is not clear if perpetuating this false narrative is convenient revisionism or simply historical ignorance. Either way, it is important to set the record straight. First, some background.

In 1969, the Patent Act was amended to permit the Commissioner of Patents to issue a compulsory license to the patent rights of any patented medicines to any person requesting it. Compulsory licenses allowed generics firms to import active ingredients to manufacture generic copies of patented brand medicines in exchange for a 4% royalty on the generic’s sales paid to the patentee. The origin of compulsory licensing dates back to the 1800s in Europe and was established to address cases where local demand of the patented invention was not being met by the patent holder or the patent monopoly was being abused in some manner. The intent was that this policy be applied on a case-by-case basis. It was never intended that compulsory licensing be applied carte blanche as a national policy. At the time of the 1969 legislation, Canada was the only developed country in the world to allow unrestricted compulsory licensing as an accepted means to control drug costs.

The compulsory licence regime in Canada allowed generic drug companies unfettered infringement of brand drug patents. Yet this regime applied only to drug patents and not to any other patented technology (e.g., aviation, telecommunications). The thinking at the time was that the pharmaceutical industry was dominated by foreign owned drug companies that had few economic ties to Canada and that a compulsory licensing regime would be an incentive for Canadian-based generic drug companies to manufacture and market cheaper copies of branded drugs. The compulsory licensing policy was successful to the extent that it created two very large and profitable Canadian generics firms (Apotex and Novopharm).

Whether the compulsory licensing policy resulted in lower drug prices or moderated drug costs is a separate matter as apart from competitive market forces there were no price control mechanisms to limit brand or generic drug prices in any way.

By the mid 1980s, it had become apparent to the Liberal governments of the day (PE Trudeau, Turner) that compulsory licensing was bad policy. Why would brand companies seek regulatory approval or market their drugs in Canada if they were to be quickly copied by generics and market share rapidly eroded by mandatory generic substitution policies?

Moreover, Canada was an outlier – no other industrialized country allowed compulsory licensing and the Canadian policy had become an irritant for trade relations with the US and Europe. But compulsory licencing was popular with vocal anti-pharma academics; and the generics industry had become highly skilled in lobbying and public relations. So, with an election coming the government punted the question to a royal commission led by Harry Eastman, an economist with the University of Toronto.

By the time the Eastman Commission issued its report in 1985, there was a new Conservative government (Mulroney) that, unencumbered by previous Liberal policies, was in a position to roll back compulsory licensing. The Bill C-22 amendments to the Patent Act were passed in December 1987 as a first step to bring Canada back in line with international intellectual property (IP) treaties.

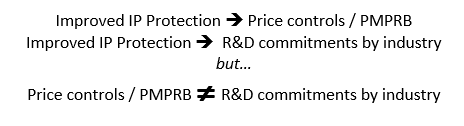

The new framework consisted of three elements. Compulsory licensing was limited but not eliminated. In exchange for improved intellectual property (IP) protection, the innovative industry committed to double R&D expenditures to 10% of sales within 10 years. In addition, given the concern that restrictions on compulsory licensing might lead to excessive prices, the industry reluctantly agreed to submit to price controls through the newly established PMPRB. Submitting to price controls were always a quid pro quo for improved IP protection but were never tied in any way to the industry’s R&D commitment. In summary:

The PMPRB price controls involve international price comparisons of prices from the seven reference countries listed in the Patented Medicines Regulations. The selection of the seven countries was negotiated between the government and industry. The revisionists would have you believe that these were all high-priced countries with significant pharmaceutical R&D infrastructures. First and foremost, it was a balance consisting of some countries with high prices and some with low drug prices. The R&D characterization was more of an afterthought recognizing that R&D countries would include both high price and low price countries.

The starting point was a dozen or so industrialized countries but never the full slate of OECD countries (the starting point for the current PMPRB consultations). Rather, the task was to create a manageable basket of (say seven) reference countries such that high price countries (which at the time included US, Germany, Denmark, Japan) would be offset by low price countries (which then and now include France, Italy, Spain). Other countries (e.g., UK, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, Netherlands) had prices that fell between the high and low-priced markets.

In the end, the post hoc rationale advanced for selecting seven reference countries was that the countries selected had R&D to sales ratios to which Canada aspired. The US and Germany were the high-priced countries offset by France and Italy as the low-priced countries with the UK, Sweden and Switzerland rounding out the seven. However, it was never suggested or even implied (as is being suggested today) that in 1988 there was a link between R&D expenditures and high drug prices or that the selection of reference countries and PMPRB’s price regulation was somehow tied to the industry’s separate Canadian R&D commitment.

If the linkage between increased R&D and high drug price is to be believed, then the industry’s “reward” for committing to increased R&D expenditures was to submit to price control legislation that did not exist prior to December 1987.

In fact, when the seven reference countries were agreed upon and listed in the Regulations in 1988, neither the government nor the industry had any sense of how prices from the reference countries would be used in practice. It was not until a year later in 1989 that the PMPRB first announced prospective price tests for its excessive price guidelines. And once established in 1990, the initial guidelines applied international price referencing on an exceptional basis with the primary focus being on domestic price comparisons.

In 1993, compulsory licencing was eliminated under the C-91 amendments to the Patent Act. In exchange, the industry made additional R&D commitments. The C-91 amendments also strengthened the price control powers of the PMPRB to address the possibility that improved IP protections might lead to excessive pricing. Again, the PMPRB’s enhanced price controls were tied to improved IP protection and unrelated to the separate R&D commitment.

In 1994, the PMPRB amended its Guidelines to reflect a new policy objective that Canadian prices, on average, should be at the median of the seven reference countries and that no product should be priced beyond the highest international price (of the seven reference countries). The PMPRB makes no mention or consideration of R&D expenditures in the analysis and rationale for the new tougher price guidelines that came into force in 1994.

Moreover, it is noteworthy that the Patent Act precludes the PMPRB from using actual Canadian R&D expenditures in regulating drug prices – instead, to the extent R&D expenditures can be considered at all, it is limited to drug specific, global expenditures on R&D prorated to Canadian sales as a proportion of global sales. So, even under the governing legislation, it makes no difference for price control purposes if all or none of the relevant R&D is actually carried out in Canada. And there are no proposals to change this treatment of R&D for price control purposes.

Indeed, the prevailing view at the PMPRB had always been that Canadian R&D should never be a basis for justifying high Canadian drug prices as there is no economic rationale for linking drug pricing to Canadian R&D. The legislation, regulations, and price guidelines reflect as much. Even Health Canada’s Regulatory Impact Assessment Statement (RIAS) accompanying the proposed Regulations acknowledges this now.

But the corollary (ignored by Health Canada and PMPRB) is that relatively low R&D expenditures cannot be the economic basis for seeking lower drug prices nor are they a justification for gerrymandering the PMPRB’s basket of reference countries.

The current proposals to amend the Patented Medicines Regulations and related changes to the PMPRB Guidelines to lower drug prices are based on a fiction that has been sold by bureaucrats to successive Health Ministers and stakeholders through an opaque and illusory consultation process where outcomes are evidently predetermined.

Price controls of patented medicines are necessary to prevent excessive pricing; however, price control mechanisms should be debated as part of open, honest and fact-based consultations where bureaucrats and politicians truly listen to stakeholders rather than simply defending the policies they appeared to have carved in stone well before the consultations began.

Neil Palmer is the Founder and Principal Consultant at PDCI Market Access Inc. and a former staffer at PMPRB. The views expressed are his own. No financial support was received from any organization for the preparation of this article.